Within Episcopal communities around the world, the rhythms of the liturgical year invite us to pause, remember, and rejoice. The Day of the Dead, or Las Días de los Muertos, alongside All Souls’ Day, is a luminous invitation to honor those who have gone before us while reaffirming the sacredness of life that remains for the living.

Though rooted in different cultural expressions, these days share a common heart: the conviction that memory is not a passive recollection but a living bond that sustains faith, hope, and love. As a parish of the Episcopal tradition, we can approach this season with a gentle, open curiosity, allowing Scripture to illumine our practices and reminding us that “the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, self-control” (Galatians 5:22-23). Our celebration becomes a way to deepen our love for God, for our neighbors near and far, and for those whom death has not severed from our lives but has reframed their presence in a new, gracious light.

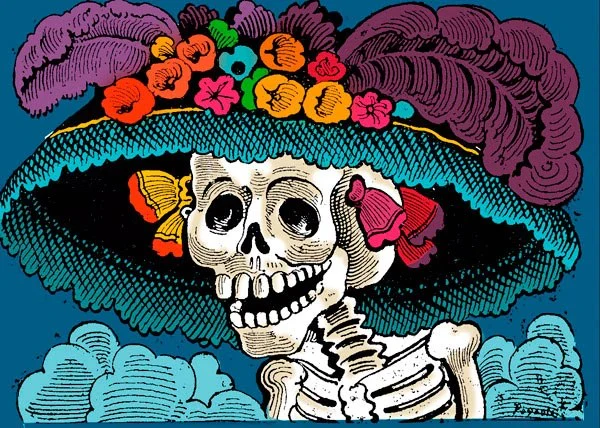

Las Días de los Muertos is a rich tapestry of memory, culture, and faith that originates in Mexico and extends its beauty across generations and borders. It begins in October and culminates on November 1st and 2nd, aligning with the observances of All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day. Rather than a period of sorrow, the days invite family and friends to come together to remember with gratitude the lives of their loved ones. Families prepare ofrendas—ofrendas are altars—adorned with photographs, favorite foods, candles, marigolds, papel picado, and personal mementos.

These offerings are not a mere memorial; they are a tangible expression of the belief that the deceased continue to accompany the living, a visitation that bridges the world of the living with the world beyond. The practice echoes the biblical call to remember and to praised, and it resonates with the Christian conviction that life overcomes death through the power of love.

Scripture speaks to the tenderness of memory and the hope that sustains us. In the Gospel of John, Jesus speaks of life beyond the grave with words that comfort and challenge: “I am the resurrection and the life. Those who believe in me, even though they die, will live” (John 11:25). This assurance—spoken in the context of Lazarus’ tomb—offers a framework for the Day of the Dead. It is not a denial of death but a proclamation that life is transformed by divine love. Similarly, Psalm 16:11 proclaims, “In your presence there is fullness of joy; at your right hand are pleasures forevermore.” The memory of the departed can become a conduit for joy if we hold it in the light of faith, recognizing that remembrance is a form of reverence that keeps our hearts open to God and to the people we love. The apostle Paul’s exhortation to live with hope—“So we do not lose heart. Though our outer nature is wasting away, our inner nature is being renewed day by day” (2 Corinthians 4:16)—reminds us that the season is not merely about clinging to the past, but about renewing the present through the love that endures beyond death.

The value of staying connected to our loved ones after they pass is a deeply human impulse, and it finds meaningful expression in Las Días de los Muertos and All Souls’ Day. The ofrenda becomes a visible sign that relationships do not end with death; they are temporarily transformed and refined in love. The candles that illuminate the altar represent prayers offered for the departed, a spiritual practice that aligns with 1 Thessalonians 5:17, which invites us to “pray without ceasing.” When families gather, share stories, and recount the quirks, kindnesses, and teachings of those who have died, they do more than reminisce. They invite those who have gone before into the present moment of family life, and they invite the living to reflect on how they might live more fully in accordance with the memory of those loved ones. In a world that often moves too quickly, this practice invites a slower, more intentional pace—one that honors the depth of human connection and the reality that love endures beyond the final breath.

There is profound joy in this celebration of life. Joy is not the absence of grief but a courageous congruence of sorrow and gratitude, a sense that for all we have lost, we have also received gifts—gifts of ancestry, of wisdom, of the capacity to love. The marigold, or cempasúchil, which brightens altars with its radiant orange hue, is often described as guiding the souls of the deceased to the offerings with its vibrant color and scent. The sensory fullness of Día de los Muertos—the music, the food, the laughter shared while telling stories about beloved relatives—becomes a medicine for sorrow, a way to acknowledge pain while refusing to surrender to it. In this way, the celebration aligns with 1 Peter 1:6-7, which says, “[Your faith] is more precious than gold… in order that the tested genuineness of your faith—more precious than gold—may be found to result in praise, glory, and honor when Jesus Christ is revealed.” The experience of allowing joy to surface amid memory can be understood as a testimony to a faith that does not shrink from the shadows but chooses to illuminate them with grace.

The concept of life as a gift is central to both Las Días de los Muertos and All Souls’ Day. The Mexican people have nurtured a gift-like understanding of death—one that invites union rather than fear, reverence rather than despair. The gentle humor and resilience often found in stories told during these days reflect a confidence that life remains meaningful, even as it is finite. This thematic thread resonates with Psalm 90:12, which urges, “So teach us to number our days, that we may get a heart of wisdom.” We are invited to count the days not with anxiety about time running out but with gratitude for the opportunities to love deeply, to forgive freely, and to live with integrity. When we recognize the fragility and beauty of life, we are more likely to cultivate mercy, patience, and generosity toward others.

As an Episcopal church community, we can celebrate Las Días de los Muertos and All Souls’ Day by embracing the universal call to remember and to love. Our liturgical and communal practices can incorporate lessons from these traditions—honoring the dead, praying for the departed, and sharing stories that reveal how those who have died shaped our faith journeys. The remembrance is not an act of nostalgia alone but a practice of faith that binds the living to the eternal. In the Epistle to the Hebrews, we are reminded of a “great cloud of witnesses” (Hebrews 12:1), a community of saints who cheer us on as we press toward the life that is in Christ. Our gatherings around the ofrenda can be framed as a humble acknowledgment that the communion of saints extends beyond the borders of time and space, inviting us to live more fully in the present with a faithful memory that guides us toward love, justice, and kindness.

If you are seeking a personal path through this season, consider creating a simple family ritual that centers on storytelling, gratitude, and prayer. Light a candle as you tell a story about someone who has died, share a small memory that reveals their character, and offer a prayer for their continued peace in God’s care. Include a few words of praise for God’s gift of life, and invite each person to reflect on how they might live more faithfully in the days ahead. In doing so, you participate in a tradition that is ancient in its longing and expansive in its mercy—a tradition that invites us to live with courage, kindness, and hope.